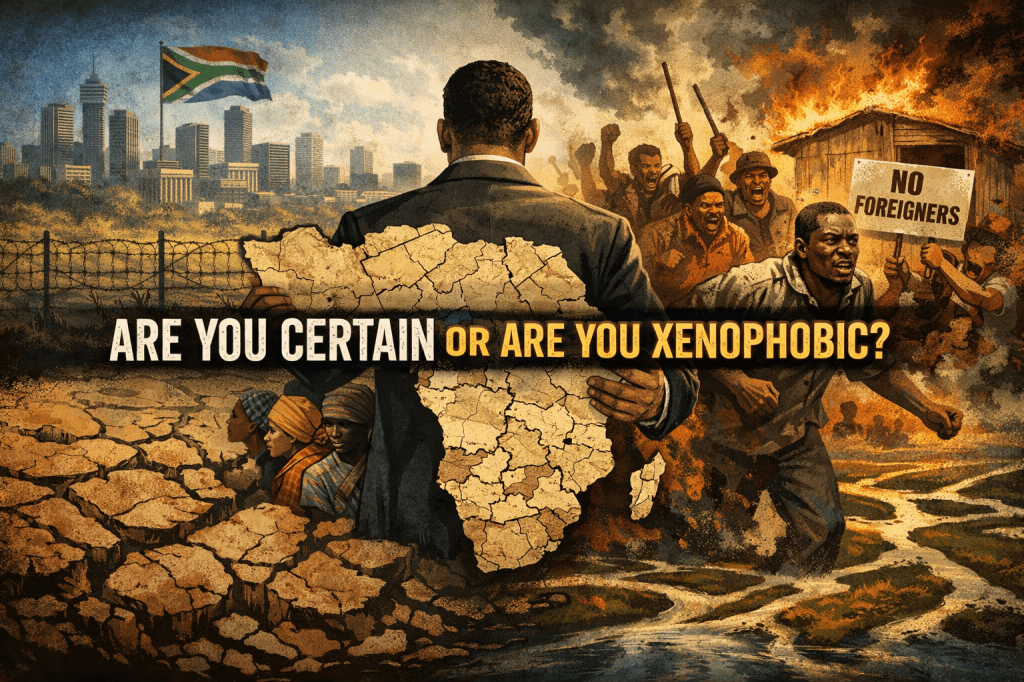

Do you believe you are superior to other Africans, or do you simply believe you know what blackness is? And if you insist that you are not xenophobic, only principled, only culturally grounded, only defending what is authentic, have you ever asked yourself where that certainty comes from, and whom it quietly expels?

Perhaps you would answer no. Perhaps you would say that South Africans are not superior, merely different. Or perhaps you would say that blackness itself has been corrupted elsewhere and preserved here, disciplined by struggle, refined by constitutionalism, modernised by a particular historical encounter with oppression.

Or perhaps, more honestly, you have never been forced to think about what you mean when you say someone is not really black, not properly African, not one of us.

This hesitation is precisely the point at which the problem begins. Blackness, in South Africa, is rarely experienced as a question. It is experienced as a conclusion. It is something many believe they can identify, defend, and police, while disavowing the violence of that policing.

ALSO READ: The Real Reason Talk Radio Sounds Tired

The language of superiority is avoided, yet the structure of superiority remains intact. It appears instead as cultural confidence, historical entitlement, or political maturity. What is rejected as xenophobia is often merely renamed as discernment.

The danger of this posture lies not in its overt hostility, but in its intellectual comfort. When blackness is treated as a fixed idea rather than a contested condition, it becomes possible to exclude without feeling cruel, to dominate without naming domination, to other Africans while insisting on solidarity in the abstract.

The South African subject does not need to say they are better. It is enough to assume that their version of blackness is the standard against which all others must be measured.

It is here, in this unexamined certainty, that the discourse of blackness ceases to describe lived realities and begins to govern them. And once blackness is governed, hierarchy follows as a matter of logic rather than malice.

While reading another article here on substack, the author introduced me to one of the most interesting metaphors known to mankind, and I will explore that metaphor to make my arguments.

Jean Baudrillard introduces one of his most arresting metaphors by borrowing from an old fable. Imagine, he asks us, an empire so obsessed with accuracy that it commissions a map of itself at a scale of one to one. Every road, every building, every contour of the land is reproduced with perfect fidelity.

ALSO READ: Unfinished Struggle for Free, Decolonised Education

The map is laid across the territory, and for a time, it appears triumphant. Nothing escapes it. Eventually, however, the land beneath begins to rot. Rivers shift, cities decay, people move.

The map does not. Long after the territory has changed, fragments of the map still remain, fluttering over a landscape that no longer corresponds to them. At that point, Baudrillard says, it is no longer the map that represents the land. It is the land that is forced to answer to the map.

For the uninitiated reader, the force of this metaphor lies in its inversion. We assume that representations come after reality, that they depend on something more solid beneath them.

Baudrillard insists on the opposite. Under conditions of simulation, representations become sovereign. They do not reflect reality. They dictate it. Reality survives only insofar as it conforms.

This is not a story about cartography. It is a story about power.

When applied to blackness, the metaphor becomes disturbingly precise. Blackness, particularly in postcolonial societies like South Africa, has been mapped obsessively.

Cultural commentators, political movements, liberation histories, and even well meaning discourses of pride have produced dense representational layers that claim to describe what blackness is.

Over time, these descriptions harden into expectations. They circulate. They are taught. They are defended. Eventually, they acquire the force of reality itself.

ALSO READ: Rebecca Oppenheimer On Leadership, Innovation & The Arts

At that point, lived black experience becomes the land that must justify itself to the map.

The danger here is subtle. The map of blackness is rarely presented as an imposition. It arrives cloaked in the language of recovery, dignity, and resistance.

We are told that to define blackness is to reclaim it from colonial distortion. Yet the logic of simulation teaches us to be suspicious of this move. Once a representation gains authority, its origins no longer matter. It begins to function independently of the lives it claims to honour.

This is what is meant when we say that blackness becomes a script rather than a story. A story unfolds. It tolerates contradiction. It allows characters to change. A script, by contrast, presupposes a role. It assigns lines. It disciplines performance. Deviations are not interpreted as creative variations but as mistakes.

In contemporary South Africa, this scripting takes familiar forms. To be black is to speak a certain way. To value certain struggles over others. To adopt particular political postures. To reject others as foreign, elitist, or contaminated. These expectations are rarely written down, but they are fiercely policed. The question “are you really black” operates as a form of social audit.

Baudrillard helps us see why resistance within this framework is so difficult. Once the map has replaced the land, appeals to lived reality sound incoherent. When someone says, “this is my experience of blackness,” the response is not curiosity but correction. The experience is measured against the template and found lacking. Accuracy no longer matters. Authority does.

South Africa occupies a particularly volatile position in this discussion. Our history of racial classification under apartheid produced some of the most rigid racial maps in modern history. Ironically, the post-apartheid period has not dissolved the impulse to define. It has redistributed it.

The apartheid state dictated blackness from above. Contemporary discourse often dictates it from within. The structure remains. Only the voice changes.

In this context, the map of blackness often presents itself as indigenous, rooted, and singular. South African blackness is imagined as a coherent identity forged through a specific history of struggle. This history is real. Its elevation to exclusivity is not.

The problem emerges when this historically specific map is mistaken for the entire territory of African blackness. Other Africans, migrants, refugees, and foreign nationals arrive carrying different histories, languages, and modes of being black. Instead of being recognised as part of a broader continental multiplicity, they are treated as distortions of the map. They do not fit the script.

This is where Baudrillard’s metaphor becomes politically explosive. Xenophobia is not merely about economic anxiety or competition for resources.

It is also about representational sovereignty. Foreign Africans are perceived as threats not only to jobs or housing, but to the authority of the map itself. They reveal, by their presence, that blackness was never singular, never settled, and never fully owned. Rather than adjusting the map, society attempts to erase the land.

One of the most corrosive effects of this representational regime is the emergence of internal hierarchies within blackness.

Once a particular version of blackness is treated as authentic, it becomes possible to rank others as derivative, backward, or excessive. This is how superiority complexes are born.

South African blackness, shaped by constitutionalism, urbanisation, and a specific liberation narrative, can come to see itself as more advanced, more modern, and more legitimate than other African identities. The irony is devastating. A discourse that claims to resist colonial hierarchies reproduces them internally.

Here the map does more than replace the land. It elevates itself. It becomes a standard against which other territories are judged. Foreign Africans are not simply different. They are framed as improperly black. Too traditional. Too loud. Too many. Too much.

ALSO READ: From Daveyton to The Operating Room: Dr. Eddie Ngwenya’s Journey

Baudrillard would recognise this immediately. When simulation takes hold, difference is not negotiated. It is expelled. Anything that threatens the coherence of the representation must be marked as excess.

Xenophobia thus becomes a form of representational hygiene. It is an attempt to protect the purity of the map by removing inconvenient realities.

The tragedy of this condition is that it impoverishes everyone. When blackness is reduced to a fixed script, South Africans lose access to the richness of continental difference. Migrants are reduced to stereotypes. Solidarity collapses into suspicion. Political imagination narrows.

More fundamentally, the insistence on defining blackness forecloses freedom. It traps subjects in identities they did not choose and punishes those who refuse to perform correctly.

It replaces living cultures with frozen images. Baudrillard’s warning is therefore not abstract. It is urgent. When representations become more real than reality, violence follows. Sometimes symbolic. Sometimes physical. Often both.

To resist this, one must do more than argue for inclusion. One must challenge the authority of the map itself.

One must insist that blackness, like the land, is always changing, always exceeding its representations, and always capable of surprising those who claim to know it best. Only then can we begin to dismantle the scripts that turn difference into danger and belonging into a border.

The most unsettling feature of South African xenophobia is not its brutality but its familiarity. It feels old. Its grammar is inherited. The demand that Africans must be the same in order to belong is not an aberration of post-apartheid anxiety but the afterlife of a colonial technology.

Empire did not merely dominate African bodies. It simplified them. It rendered difference illegible so that governance could proceed without complication. Africans were made interchangeable not because they were the same, but because sameness made them manageable.

What should trouble us is how easily this logic reappears under the sign of liberation. The vocabulary has changed. Where colonialism spoke of primitiveness and incapacity, contemporary discourse speaks of culture, authenticity, and political maturity.

ALSO READ: Sovereignty vs Proxy: Venezuela and the Global South’s Unfinished Struggle for Self-Rule

Yet the structure remains intact. Blackness is still expected to present itself as coherent, unified, and recognisable. Difference remains an inconvenience, now framed not as inferiority but as deviation.

The superiority complex that accompanies this posture is rarely named as such. It appears instead as confidence, as modernity, as having arrived where others have not.

South African blackness is imagined as more disciplined, more enlightened, more advanced. The irony is severe. A discourse forged in resistance to racial hierarchy reproduces hierarchy internally.

Continental difference is collapsed into a ranking system. South Africa is at the apex. Other Africans are positioned as excessive, unruly, or insufficiently modern.

This logic explains why debates about language, queerness, class mobility, and education provoke such intense policing within black communities. These differences threaten the illusion of coherence upon which representational authority depends.

They reveal that blackness is not a settled identity but a restless terrain. The response is not curiosity but correction. Not engagement but discipline. To deviate is to betray.

To borrow a metaphor suited to this context, blackness is not a single river flowing predictably toward a common destination. It is a delta, branching, converging, splitting again, shaped by terrain, climate, and time. To insist on a single channel is not to preserve the river. It is to dam it. Rivers flow in one direction.

They suggest destiny. Blackness is closer to a delta, shaped by history, geography, and contingency.

To insist on a single channel is obstruction. It dams the flow of difference in the name of order. Xenophobia is one of the inevitable pressures that builds behind such a dam. When difference can no longer move, it is either expelled or destroyed.

What follows from this is not the need for a better definition of blackness, but the courage to refuse the demand for definition itself.

Every attempt to refine the map simply reproduces the violence it claims to correct. Refusal, by contrast, is not emptiness. It is generative. It creates space for blackness to be lived rather than proven, inhabited rather than performed. It allows Africans to exist without submitting to a test of authenticity administered by those who have mistaken representation for reality.

To say that blackness has no single definition is not to evacuate it of meaning. It is to return meaning to those who live it. It is to insist that blackness is produced through experience, relation, and struggle, not dictated by authority or guarded by borders.

In Deleuzian terms, blackness must be approached as becoming, as movement without an original to protect.

In Baudrillard’s terms, the task is to tear the map, not in order to lose our way, but to remember that the land was always alive beneath it.

If this unsettles you, if it feels like a loss of certainty, that discomfort is not a failure of the argument. It is its demand. To confront xenophobia and superiority in South Africa requires more than moral condemnation. It requires an intellectual reckoning with the desire to stabilise blackness, to own it, to police it.

Until that desire is named and refused, the map will continue to harden, and the land will continue to be sacrificed in its name.

Leave a reply to The Child Who Is Not Held By The Village Will Burn It To Feel Its Warmth – The Joburg Reporter Cancel reply