There is an old African proverb we recite with ease and abandon: “The child who is not held by the village will burn it to feel its warmth.” It is usually invoked as cultural colour, a reminder of communal responsibility, a nostalgic echo of who we once were. In South Africa today, that proverb no longer reads like inherited wisdom. It reads like indictment. It reads like warning. It reads, increasingly, like prophecy.

At the intersection of Spine Road and Mew Way in Khayelitsha, just after sunrise, a boy no older than thirteen moves between cars with a small packet of biscuits. His school bell rang long ago. His peers are seated in classrooms reciting times tables, copying notes, preparing, however imperfectly, for a future still open to them. He is already negotiating adulthood. Already learning that survival requires alertness, not literacy. When a driver shakes his head, the boy steps back without complaint. He has learned something early, and he has learned it well: insistence invites punishment; invisibility keeps you safe.

This scene is not unique to Khayelitsha. It is repeated daily in Soweto, Umlazi, Mdantsane, Botshabelo, Galeshewe and Mitchells Plain. Boys at robots. Boys at taxi ranks. Boys lingering at school gates long after the bell has rung, not because they are late, but because they are no longer enrolled. They were once learners. Once counted. Once spoken of in terms of potential. Somewhere between the early grades and adolescence, they slipped out of the system quietly, without ceremony, without alarm.

South Africa has learned to live with this disappearance. That should trouble us deeply.

ALSO READ: Rebecca Oppenheimer On Leadership, Innovation & The Arts

Every January, the nation gathers around matric results with justifiable pride. We celebrate improvement, resilience and progress, and we should. The story of the South African girl child is one of the most profound victories of our democratic era. A generation ago, girls were systematically denied education, discouraged from ambition, burdened with domestic labour and cultural silence. Today, girls outperform boys in matric participation, Bachelor-level passes and university admissions. This is not accidental. It is the result of deliberate policy, sustained advocacy and moral clarity. It deserves applause.

But celebration without reflection becomes complacency.

Because hidden behind those results is another story, less visible but more dangerous: by the time learners reach matric, boys are already missing in alarming numbers. Girls now form the majority of candidates and an even greater share of top passes, while boys dominate repetition and dropout statistics from as early as intermediate phase. Tens of thousands of boys who start school every year will never write a final examination. This is not a performance gap. It is an exit crisis. It is attrition on a national scale.

The consequences follow with brutal consistency. Young men constitute the majority of the unemployed, the incarcerated, the violently injured and the dead by suicide. Over ninety percent of South Africa’s prison population is male. Nearly four out of every five suicides are men.

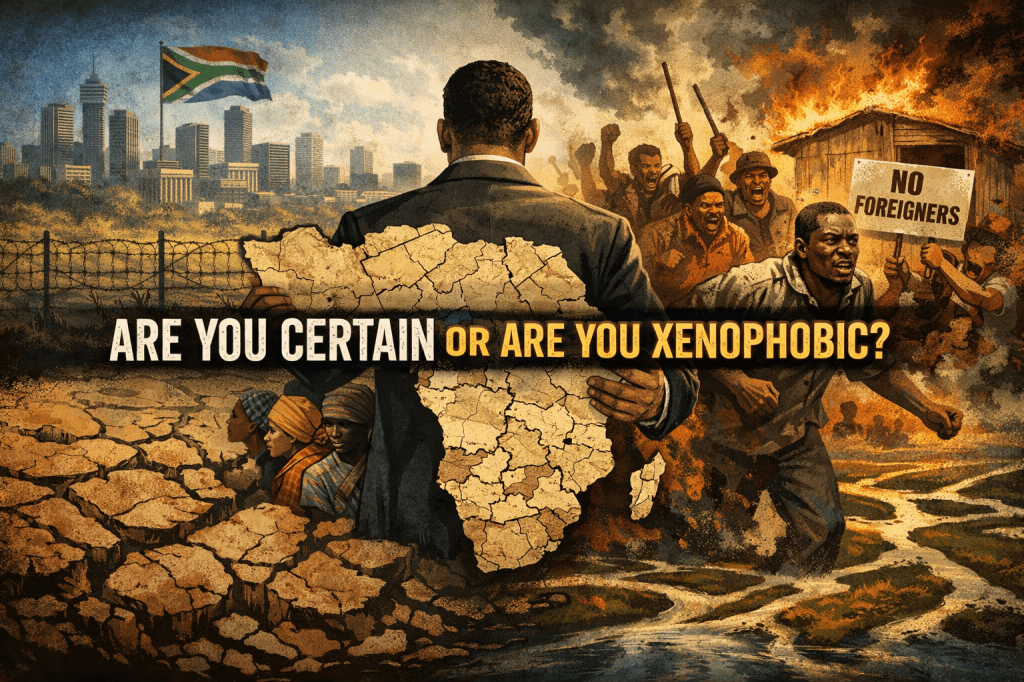

ALSO READ: Are you certain or xenophobic? Either one is wrong

These outcomes are not random, nor are they purely criminal or economic phenomena. They are the long-term consequences of early disengagement, be it educational, emotional and moral, compounded over time by neglect masquerading as neutrality.

A high school principal in Soweto, who has spent over twenty-five years in public education, put it plainly: “By the time a boy reaches Grade 9 already labelled as ‘a problem’, we are no longer educating him, we are managing him. And once a child feels managed instead of believed in, you’ve already lost him.”

South Africa’s schooling system, for all its intentions, was not built with developmental reality at its centre. It rewards stillness, sustained abstraction, emotional containment and verbal articulation.

Many children adapt. Many boys, particularly those growing up amid poverty, instability and father absence, do not. Not because they lack intelligence or ability, but because their development unfolds differently. Their energy arrives early. Their appetite for risk precedes their impulse control. Their bodies mature before their patience does. Instead of recognising this as part of becoming, the system often treats it as misconduct.

Ms Nomsa Dikweni, a Foundation Phase teacher in the Eastern Cape with eighteen years’ experience, described the pattern with quiet exhaustion: “The boys are not stupid. They are curious, physical, loud, impulsive. But the system does not know what to do with that. So we discipline it out of them, or we push them out altogether.”

Once a boy internalises the idea that school is a place of constant correction rather than growth, disengagement is no longer rebellion. It is retreat.

Layered onto this educational reality is South Africa’s profound fatherhood crisis. More than sixty percent of children do not live with their biological fathers.

ALSO READ: Classrooms of Blood: The Assassination of South Africa’s School Leaders

For many boys, there is no sustained male presence to interpret failure, model restraint or translate anger into purpose. A father, or a credible male figure, does not merely provide materially. He provides meaning. He teaches a boy how to lose without collapsing, how to delay gratification, how to absorb correction without humiliation.

If you trace the stories back far enough, most of the young men here started falling apart long before they committed a crime. Many of them never had a man to correct them without beating them, or to believe in them without fear.

Traditional African societies understood this danger instinctively. Among amaXhosa, Basotho and Tswana communities, boyhood was guided deliberately through elders, age-sets and initiation processes that taught endurance, accountability and service. These were not mere cultural rituals; they were systems of moral jurisprudence. A boy was not left to improvise manhood. Failure was expected, but never ignored. Restlessness was anticipated, but redirected. Strength was cultivated, but always yoked to responsibility.

Modern Africa dismantled these systems without replacing them. We replaced communal formation with overstretched classrooms, abstract curricula and moral silence. We told boys what not to do, but rarely who to become.

The philosopher Hannah Arendt warned that “education is where we decide whether we love our children enough not to expel them from our world.” Too many South African boys have been expelled, not formally, but functionally.

When boys drop out of school, they do not float harmlessly on the margins. They enter informal economies early. They are recruited into gangs that offer what institutions withheld: belonging, hierarchy and recognition. They learn violence as language because no one taught them vocabulary for frustration. By the time society encounters them again, it is through police vans, court rolls and correctional facilities.

We keep expanding prisons as if crime appears at twenty-five. These men didn’t suddenly fail as adults. They were failing quietly as children.

Other jurisdictions have begun to confront this reality openly. In parts of Europe and North America, governments now speak explicitly of a boys’ education crisis, introducing early mentorship, alternative pathways and targeted support. South Africa remains hesitant, as if acknowledging male decline somehow threatens the hard-won progress of women. It does not.

This is not a zero-sum reckoning. The advancement of the girl child remains one of our greatest democratic achievements. But justice loses coherence when it abandons balance. Empowered women cannot thrive in a society saturated with male despair. Social cohesion fractures when large numbers of young men feel unnecessary, unseen and unformed.

And yet, this is not merely a story of loss. It is also a story of extraordinary, squandered potential.

When boys are formed well, they anchor societies. They build economies, maintain infrastructure, innovate, farm, teach, protect and create. They take risks that expand nations and shoulder responsibility when it is taught early and consistently. A country that integrates its boys gains stability, productivity and hope.

South Africa cannot afford to squander this resource.

What is required now is not another policy document drafted in careful language and forgotten in filing cabinets. It requires a national pause, a constitutional moment of reflection. Early intervention that recognises developmental reality rather than punishing it. Male mentorship embedded in primary schooling. Dignified vocational and technical pathways that restore purpose to non-academic excellence. Community responsibility for formation, not just certification.

The boy at the robot in Khayelitsha is not asking only for spare change. He is asking whether this country still has a place for him.

And how South Africa answers that question will determine whether the proverb remains wisdom – or becomes our epitaph.

Thanks for reading! Make sure to hit that subscribe button below!

Leave a comment