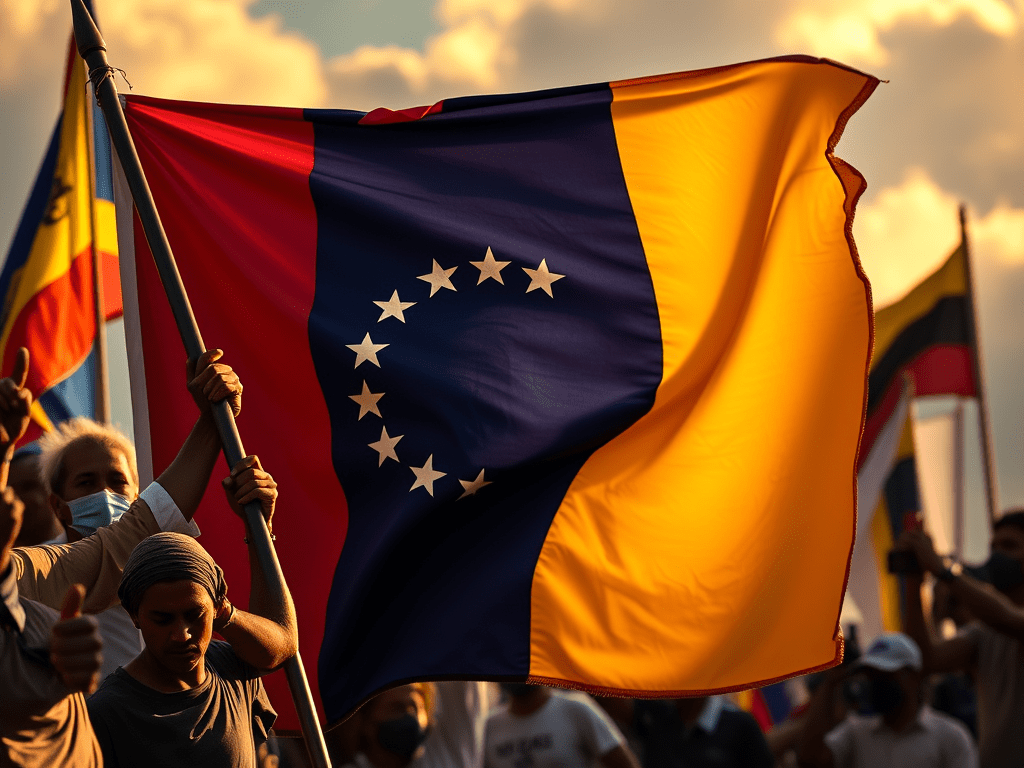

When a nation’s fate is debated more passionately in foreign capitals than in its own public squares, sovereignty itself becomes the casualty.

Venezuela today is not merely negotiating succession; it is engaged in a far more consequential struggle, the collision between internal legitimacy and external validation. This is not simply a Venezuelan crisis. It is a familiar condition of the post-colonial world, where power speaks in the language of democracy while practicing the politics of dominance.

For Africa, Latin America, and much of Asia, this drama is well known. It is the theatre in which sovereignty is applauded in principle but rationed in practice; where elections are praised, questioned, or dismissed depending not on their credibility alone, but on their geopolitical usefulness.

ALSO READ: Venezuela’s Defiance: The Quiet War Over Sovereignty

Two Legitimacies, One Country

Venezuela exists today under dual and competing regimes of legitimacy.

On one axis lies internal authority: control of the state apparatus, courts, electoral bodies, security institutions, and constitutional form. On the other lies external recognition: endorsement by powerful states, access to international finance, sanctions relief, and diplomatic legitimacy.

In theory, democracy reconciles these two. In practice, the Global South has learned that they often pull in opposite directions.

ALSO READ: 8 Questions for KING THA – Thandiswa Mazwai

Africa has lived this contradiction repeatedly. Governments that command domestic support but resist global economic orthodoxy are branded pariahs. Others, embraced abroad but hollow at home, govern in a permanent legitimacy deficit, sustained through aid dependency, securitisation, and external patronage.

Venezuela now stands at this exact fault line.

María Corina Machado and the Politics of Acceptable Opposition

To Western capitals, María Corina Machado is legible power. She speaks the grammar of liberal democracy fluently: institutional reform, market confidence, electoral legitimacy, and reintegration into the global order.

Internationally, she is framed as the embodiment of Venezuelan popular will, the moral counterweight to authoritarian decay. Her legitimacy is cast as electoral, ethical, and urgent.

Yet internally, the picture is more complex.

To many Venezuelans, Machado represents courage and resistance. To others, she evokes an elite political tradition historically distant from the material suffering of the poor. And to a significant constituency shaped by decades of anti-imperialist struggle, her proximity to U.S. endorsement provokes a deeper anxiety:

Is this emancipation or substitution?

This is not an accusation. It is a perception. And in politics, perception often determines durability.

The Global South knows this dilemma well: when opposition is rewarded primarily because it reassures external interests, it risks losing organic legitimacy at home.

The Proxy Problem and the Colonial Echo

The language has changed, but the logic remains disturbingly familiar.

Where colonial administrations once appointed governors, today recognition, sanctions, and “democratic benchmarks” perform the same sorting function. Leaders are not conquered militarily but economically disciplined; not overthrown by decree but by delegitimisation.

Africa’s history is littered with examples.

- Patrice Lumumba, democratically elected, was removed because Congolese sovereignty threatened Western mineral interests.

- Kwame Nkrumah, overthrown while abroad, warned presciently: “Neo-colonialism is the worst form of imperialism. For those who practice it, it means power without responsibility; for those who suffer from it, exploitation without redress.”

- Thomas Sankara, assassinated for insisting that Africa must “consume what it produces,” paid the ultimate price for ideological insubordination.

Latin America offers its own parallels from Salvador Allende to Jacobo Árbenz. Venezuela’s oil wealth places it squarely within this historical pattern: resource-rich states are rarely permitted ideological autonomy.

Their sovereignty is treated as conditional.

International Law: Principle or Instrument?

International law is invoked relentlessly in the Venezuelan crisis but applied selectively.

The UN Charter enshrines:

- Sovereign equality,

- Non-intervention, and

- Self-determination of peoples.

Yet in practice, these principles bend under geopolitical pressure.

Sanctions, legally framed, function as economic sieges, devastating civilian populations while entrenching ruling elites. Recognition is extended not after constitutional resolution, but in anticipation of preferred political outcomes.

For the Global South, this reinforces a bitter lesson: international law increasingly operates as a flexible geometry of power, not a neutral arbiter.

Frantz Fanon warned of this moment:

“The colonial world is a world divided into compartments… the logic of this world is carried into independence unless it is consciously dismantled.”

Venezuela is confronting that inherited logic in real time.

ALSO READ: Understanding Elite Influence in South Africa’s Crisis

Authority Without Affection: The Incumbent State

On the other side of the legitimacy divide stands the Maduro-aligned state apparatus, a familiar post-liberation pathology.

Here, legal form survives while constitutional spirit decays. Control of institutions substitutes for consent; historical legitimacy is mistaken for permanent entitlement.

Africa knows this pattern well, from Zimbabwe to Equatorial Guinea, where liberation credentials fossilise into ruling entitlement, and law becomes an instrument of survival rather than justice.

The tragedy is that such regimes often endure not because they are trusted, but because their alternatives are perceived as externally authored.

The People: Hostages of a False Binary

Caught between externally validated opposition and internally entrenched authority are ordinary Venezuelans, exhausted, impoverished, and politically marginalised.

They seek neither ideological purity nor geopolitical alignment. They seek:

- Food before free-market sermons

- Stability before slogans

- Dignity before doctrine

Yet proxy politics silences them. The nation becomes a chessboard; its people, collateral.

Steve Biko’s words echo here:

“The most potent weapon in the hands of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed.”

Proxy politics weaponises despair, forcing populations to choose between bad governance and externally managed alternatives.

Africa’s Mirror: Case Studies in Conditional Sovereignty

Venezuela’s crisis should unsettle Africa deeply.

- Libya demonstrates how humanitarian intervention can dissolve the state itself.

- The DRC shows how sovereignty collapses when mineral wealth attracts perpetual external arbitration.

- Zimbabwe illustrates how sanctions harden elites while immiserating citizens.

- Burkina Faso and Mali reveal the resurgence of nationalist backlash when democratic legitimacy is perceived as foreign regulated.

Across these cases, the lesson is consistent: sovereignty that lacks economic independence, institutional credibility, and popular legitimacy will always be vulnerable to external management.

Beyond the False Choice

The binary presented to Venezuela, authoritarian nationalism versus externally endorsed democracy, is false and dangerous.

True sovereignty is neither isolation nor submission. It is self-determined legitimacy, constructed through:

- credible institutions,

- accountable leadership, and

- economic models that preserve national dignity.

Thomas Sankara captured it succinctly:

“He who feeds you, controls you.”

Political freedom without economic autonomy is fragile. Democracy without social justice is performative.

The South Remembers

Venezuela’s quiet war is not an aberration. It is a symptom.

The Global South remembers when sovereignty was denied outright. Today, it is merely licensed, conditional upon good behaviour as defined elsewhere.

Venezuela’s struggle is therefore not only Venezuelan. It is part of an unfinished decolonisation — one where flags have changed, but hierarchies endure; where the vocabulary of democracy is fluent, persuasive, and profoundly unequal.

Until legitimacy is allowed to grow organically from within societies, rather than being certified abroad, crises like Venezuela will persist.

ALSO READ: How South Africans Plan to Travel Bigger in 2026

Not as failures of democracy.

But as indictments of a global order that still fears truly sovereign peoples.

Leo Ndumiso Maphosa is a legal scholar and Pan-African political analyst whose work interrogates sovereignty, democratic legitimacy, and global power asymmetries. His writing situates contemporary crises within the enduring and unfinished project of decolonisation.

Leave a comment