A “National Dialogue” that ignores those who reject it is less about listening and more about staging unity for the cameras.

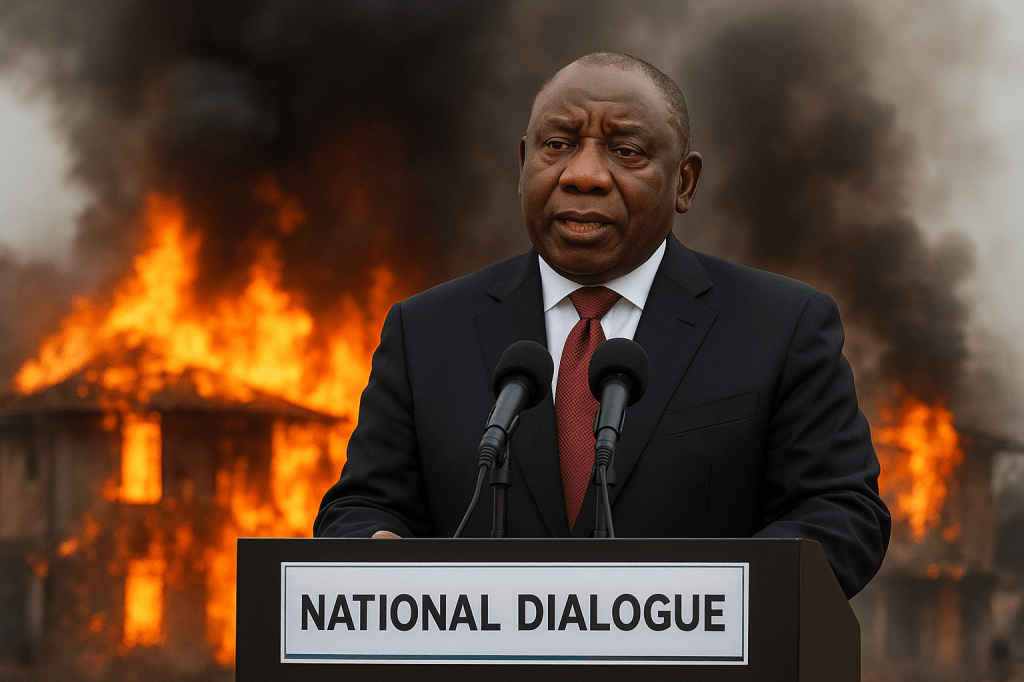

In the grand hall where South Africa’s National Dialogue was launched, President Cyril Ramaphosa stood before the nation, speaking of unity, reconciliation and a “shared vision for our future.” Cameras clicked, ministers nodded, and the official programme rolled on.

Outside that curated frame, the country was still burning, not just in the metaphorical sense, but literally, in shack settlements gutted by fire, in service delivery protests, and in the smouldering anger of millions who feel unseen.

The contrast is striking: a stage managed for hope, while the lived reality of the poor remains one of survival and exclusion. As a researcher, I am reminded of Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth, where he warns that when the voices of the marginalised are ignored, their grievances will not vanish, they will erupt, often in ways the political establishment deems “irrational” or “violent.”

My master’s research examined why marginalised groups sometimes turn to violence as a form of communication. The findings were unsettling: for many, violence was not a first choice, but a last resort, the only language they believed the state would hear. When peaceful petitions go unanswered, when councillors are absent, when the formal “invitation” to democratic participation is a thinly veiled formality, fire on a street corner becomes a statement that cannot be ignored.

Fanon argued that under systems of structural oppression, violence is not merely destructive; it is expressive. It is a political language forged in the absence of genuine dialogue. Yet here we are, hosting a “National Dialogue” that risks becoming the very thing it claims to replace, a conversation among elites, insulated from the realities it purports to address.

And here lies the irony: a government intent on launching a national conversation has not listened to, or even acknowledged, the many South Africans who have openly said they do not want it. Ignoring dissent at the very inception of a “dialogue” strips it of its purpose. This is not engagement; it is performance. And like any well-rehearsed play, disruptive voices are kept firmly outside the theatre doors.

Recent months have seen an upsurge in protests across the country, from Soweto to Mitchells Plain, where communities have blocked roads, burned tyres, and occupied municipal buildings to demand water, electricity, and safety. These are not the acts of people desperate to join a conference in a hotel ballroom. They are the cries of citizens who have already concluded that the state does not listen unless it is forced to.

A real dialogue would look and feel different. It would take place in community halls, taxi ranks, and informal settlements, not just in conference venues. It would treat anger as a valid political emotion, not a threat to be policed. And most importantly, it would commit to tangible action beyond rhetoric, because promises, like photographs, can be beautifully framed yet completely hollow.

If the National Dialogue is to matter, it must stop speaking about the people and start speaking with them, even, and especially, when they say they want no part in it. Otherwise, South Africa will continue to perfect the art of talking while the flames, literal and figurative, rise ever higher.

About the author

Sibonelo Mavuso is a political communications researcher and communications and advocacy professional. They hold a Master’s degree from the University of Cape Town, where their research examined why marginalised groups in South Africa sometimes resort to violence as a form of communication. Their work is informed by a deep interest in social justice, public discourse, and bridging the gap between policy and lived experience.

Leave a comment